A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Meditation for Work Stress, Anxiety and Depressed Mood in Full-Time Workers

Research submitted by:

R. Manocha,1 D. Black,2 J. Sarris,3,4 and C. Stough4

1Discipline of Psychiatry, Sydney Medical School, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney University, St Leonards, NSW 2065, Australia

2Faculty of Health Sciences, Cumberland Campus C42, The University of Sydney, P.O. Box 170, Lidcombe, NSW 1825, Australia

3Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3121, Australia

4NICM Collaborative Centre for Neurocognition, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia

Introduction

Health professionals, consumers, and patients are becoming increasingly enthusiastic about meditation; a survey of Australian GPs in 2000 found that almost 80% of respondents had recommended meditation to patients at some time in the course of their practice [1].

A nationally representative survey of US households indicated that almost 1 in 5 consumers had used some form of “mind-body therapy” in the past 12 months, of which meditation was the commonest method [2].

While a survey of cancer sufferers in the UK found that meditative practices were the most popular complementary therapy used by this patient group [3].

The vast majority of research into meditation is focused on stress-related issues and indeed much of the enthusiasm amongst both health professionals and the general community is derived from these reports.

Is meditation effective in reducing occupational stress, and if it is, is it more effective than placebo?

Do different approaches to meditation have different effects?

Discussion

This study has a number of strengths that assert progress in the field of meditation research.

First, the use of a large sample, and rigorous methodology, particularly the efforts taken to exclude the effects of nonspecific factors is a notable methodological strength. This is one of the largest RCTs to make an earnest attempt to control for nonspecific effects and one of the only independent RCTs to compare two different conceptual understandings of meditation.

Second, in this study there was no evidence of adverse effects associated with either intervention since both intervention groups generated significantly fewer negative responders than the untreated group. This is an important though often neglected consideration.

Third, this study provides evidence to suggest that a “mental silence” definition of meditation is more likely to be associated with specific benefit. The implications of this third point are particularly fascinating, and we discuss some of them below.

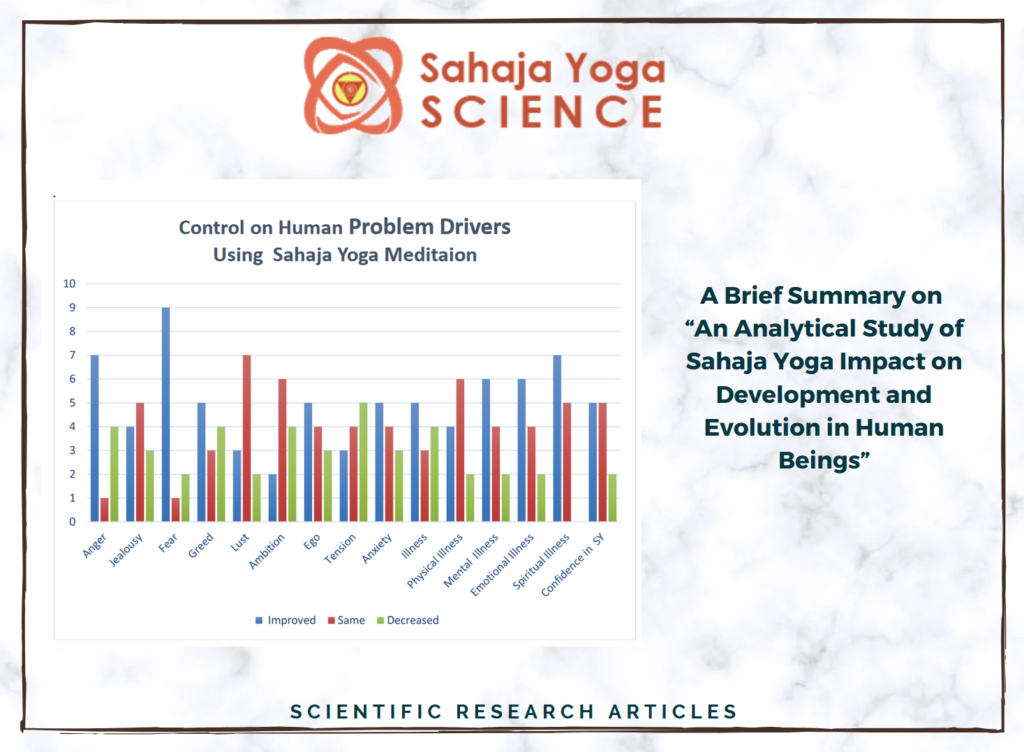

A differential effect across the two intervention groups compared to nontreatment was found in this study. Our findings indicate that the mental silence-orientated approach is specifically effective in reducing work-related stress and depressive feelings.

A field study in which 293 medical practitioners were taught a meditation skill based on Sahaja yoga for the enhancement of psychological well-being made a number of important observations with regard to the relationship between mental silence and the study outcomes [27].

The relationship between participants’ self-reported experience of “mental activity/silence” and their self-reported experience of “calm/peaceful” and “tension/anxiety/stress” was strong and highly significant, such that the more that participants’ mental activity moved toward the silent state, the more calm/peaceful (, ) and the less tense/anxious/stressed they felt (, ).

In the diary card data, a significant relationship between self-rated mental silence and K10 score such that a higher self-rated score of mental silence was associated with a lower level of psychological distress (i.e., a lower K10 score). Among those GPs who regarded the intervention as highly effective, there was a significant positive relationship between the change in mental silence rating and change in K10 score. Taken together, (this study and Manocha’s field study) suggest an effect not simply attributable to relaxation or placebo, indicating that “reduction of thought activity” has particular effectiveness for the reduction of stress and stress-related illness.

Conclusion

This study provides preliminary evidence to support the use of a mental silence form of meditation called Sahaja Yoga to reduce work stress and depressed mood.

While the results are encouraging, further research is now required to validate and explore these findings. Given the low-cost, noncommercial nature of the intervention, and the low risk of adverse effects it would not be unreasonable to suggest that this meditation would be useful as a health enhancing strategy with potential for significant socioeconomic benefit to individuals and society.

This trial provides initial evidence indicating that there are measurable, practical, and clinically relevant differences between two differing conceptualizations of meditation.

On a practical level Sahaja Yoga, and by inference, possibly any meditation technique that is specifically mental-silence oriented, is safe and effective as a general intervention strategy for dealing with work stress.

It suggests that those forms of meditation that emphasize “thought reduction” or “mental silence” may have specific effects beyond simple relaxation techniques that may be relevant to health care.

The fact that this trial was a field study of a group with demonstrably higher levels of psychological distress when compared to available population norms strongly suggests that the intervention is feasible and relevant in the “real world”.

Read Entire Report – https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2011/960583/